Cold Places

November 2025

If I move a block of stone into the green wood sector of the bagua, will my children grow up to be dull? If I put my desk next to a window, will my thoughts become insipid? Where is the dragon sleeping? Practitioners of feng shui, the Chinese art of geomancy, worry about such things—and not least whether in calculating the most propitious placement of a building, the orientation should be to magnetic north or to true north.

North, to a proto-Indo-European traversing the steppes a few thousand years back, was simply the direction the left hand pointed in when one faced the rising sun, a position that changed throughout the year. Our notion of north is based on a finer but still inexact science, its core assumption that we live on a perfect orb that spins along at a uniform rate. We do not, and it does not. Still, true north is a geometric concept that posits a line, a meridian, wrapping neatly around the planet. Also called geodetic north, it is constant to the extent that, for our lifetimes, it points pretty much toward Polaris, our north star for the next few thousand years.

True north, in other words, does not really exist in nature. Neither does grid north, a term used in mapmaking to account for the difference between north on a presumed round Earth and north on a flat map. In most places the variations between true and grid north are minor, but substantial enough that they’re noted on modern maps. Astronomic north is formally calculated from the vertical direction of gravity and the axis of rotation of the planet, and not, as is true north, from its presumed roundness; the difference between astronomic and geodetic north is called the LaPlace correction, used mostly by surveyors.

Among all the different norths, including record and assumed, the most important, if only because the most real, is magnetic north. Consult a compass, and unless weird circumstances obtain, the point toward which the needle freely spins is the north magnetic pole, the place—now geodetically north of Canada’s Axel Heiberg Island—where the planet’s northerly magnetic field intersects with the surface. This pole wanders by tens of miles each year, yielding a cartographic problem that cries for constancy. Thus, presto, the polite fiction of geodetic and grid norths.

True north and magnetic north, the differences between which are measured by an angle of declination, are the same only here and there on the planet, including points along an agonic line that stretches from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic and that for much of its southern course more or less coincides with the Mississippi River valley. Another is said to lie within the eerie area called the Bermuda Triangle, a place of many navigational errors and not a few shipwrecks and downed planes.

If you travel there, you don’t have to bother changing your iPhone’s compass setting to “Use true north,” as you might want to do elsewhere in your wanderings. Just watch the reefs. Or, elsewhere, the Guernseys, since cows seem to have an uncanny propensity for aligning themselves toward geomagnetic north as they browse. Call it bovine feng shui.

1909: The Year of the Poles

In the annals of world exploration, few names resound so honorably as that of Ernest Henry Shackleton. Born in southern Ireland in 1874, he knew from boyhood that his destiny lay on the sea. Pressed by his parents to become a doctor, he longed for a posting in the English navy, but such options were not easily open to the Irish in those days, even if his family origins lay in thoroughly British Yorkshire. Undeterred, Shackleton joined the merchant marine and proved himself so invaluable that, when he was 27, he was invited to enter the Royal Navy reserve corps. There Captain Robert Falcon Scott, himself a brilliant and fearless explorer, took notice of him, enlisting Shackleton in his British National Antarctic Expedition and making sure that the tireless Shackleton was at his side when he sledged his way across the Ross Ice Shelf and reached southerly extremes no human had ever before seen.

Shackleton, unfortunately, also had a habit of working himself into exhaustion and illness. No sooner had the Scott party reached those latitudes than did he have to leave the continent, felled by scurvy, for a long recovery back in England and Ireland. Five years later, he was in full health again, and now he traveled back to Antarctica, this time as the leader of the British Antarctic Expedition in command of a beat-up old ship called the Nimrod.

In August 1907, Nimrod sailed to New Zealand, where another vessel towed it south into Antarctic waters so that Shackleton’s vessel could conserve coal, which would soon become scarce. Like Scott, Shackleton had an eye for talent, and he recruited Douglas Mawson, an Australian geologist whose name is also enshrined in Antarctic history, as well as a brave but, at 50, rather old lieutenant, Edgeworth David. He had hoped to guide these men and the rest of his crew into the Bay of Whales, with its broad and comparatively gentle anchorage, but when they arrived in January 1908 the bay was so congested with icebergs that he had to take Nimrod to McMurdo Sound, where it unloaded a complement of ponies and an automobile that had been carefully fitted for cold-weather conditions—a good thing, since the temperature was still hovering at –4° F.

Shackleton set about surveying the area around McMurdo and climbing 13,200-foot-tall Mount Erebus, a great volcano that dominated the horizon. Then he and his crew hunkered down for an Antarctic winter, which they spent peaceably, planning for the spring. When the warmer season arrived, they put their plans into motion: Shackleton and three men would make for the South Pole, while David and two companions, including Mawson, would make for the magnetic pole. Shackleton gave David the car, certainly a generous gesture, even if it proved to be prone, strangely enough, to constant overheating. On September 25, David set off for the south magnetic pole, more than 1,200 miles distant. He did not reach it until January 15, but all were safe, and all returned safe to Nimrod.

For its part, the Shackleton party left on October 29 and immediately encountered problems. A pony kicked one of the men, breaking his leg just below the knee. The men took quiet revenge when, some weeks later, their rations ran short and they turned to horsemeat for survival. More ponies fell, and then the men began to eat the grain the ponies would have used. On November 26 they reached the point that Scott and Shackleton had reached six years earlier; a month later, they reached the 10,200-foot-tall polar plateau, met ferocious blizzards and hurricane-force winds, and finally, heartbreakingly, were turned back only 97 miles from the South Pole. “I thought, dear, that you would rather have a live ass than a dead lion,” Shackleton wrote to his wife on returning to Nimrod, this time on foot, all the ponies having been used up. He and his companions had walked 1,700 miles, claiming a huge expanse of land for the British Empire.

Shackleton did not achieve his goal in 1909, but he achieved something few polar explorers could boast of: thanks to his good leadership and careful planning, not a single person died. So it was when he returned to the Antarctic in 1914 aboard the ship Endurance. That ship broke up on the ice, and he had to lead his 27-man crew to safety over a nightmarish, two-year-long course. He did so through a combination of hard-nosed rules—there would be no fighting, no unnecessarily taken risks, and no shirking of duty—and his own willingness to plunge in and do the dirtiest, most unpleasant of jobs without complaint. Moral but not pious, disciplined but not humorless, he inspired the love and absolute confidence of his men, and even the weakest and least trustworthy pulled his weight.

On January 5, 1922, Ernest Henry Shackleton died at Grytviken, South Georgia, the launching point for yet another Antarctic expedition. He had worn himself out working to raise funds for the crew, but not before leaving behind two classics of polar exploration, The Heart of the Antarctic and South.

Born in 1856 and inclined to a certain imperiousness, Robert Edwin Peary inspired no such confidence in his men. The beginning of 1909 found him racing to make the North Pole before Shackleton reached the South Pole—and, indeed, one of the reasons Shackleton climbed to the top of Mount Erebus was to best Peary’s claim of having reached the farthest latitude, a feat he had accomplished in 1905.

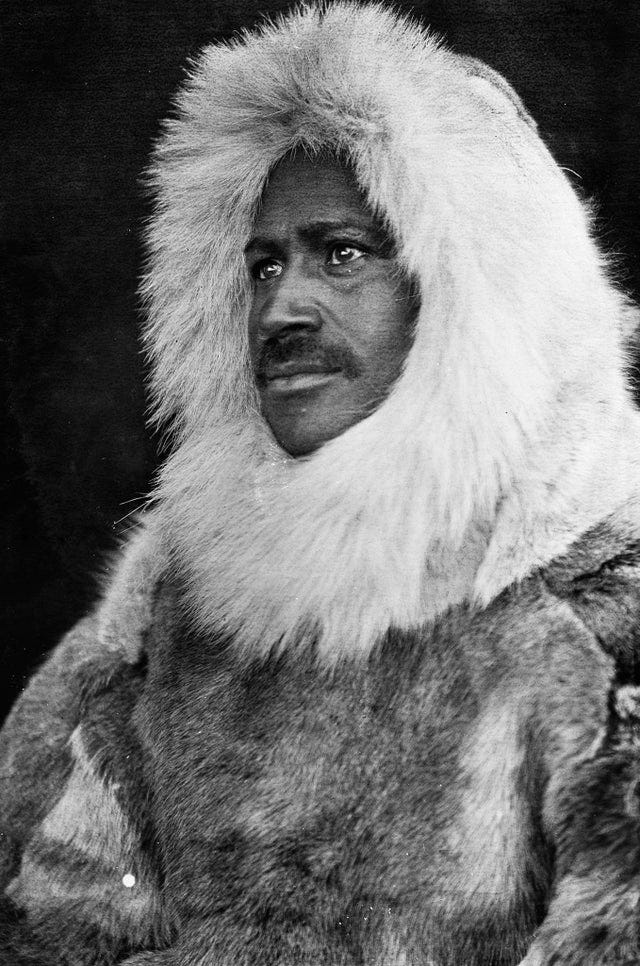

Peary, an officer in the US Navy, was indisputably a great explorer, even if perhaps too openly hungry for fame. Working with an African American naval engineer named Matthew Henson from 1886 until his death in 1920, Peary charted huge expanses of the Far North and, among other things, provided the first incontrovertible evidence that Greenland was an island. Exploring the Greenland ice cap led him to conclude that the North Pole lay still farther north, and was not, as had long been presumed, part of that territory. He resolved to become the first man to reach the pole, no matter what it took.

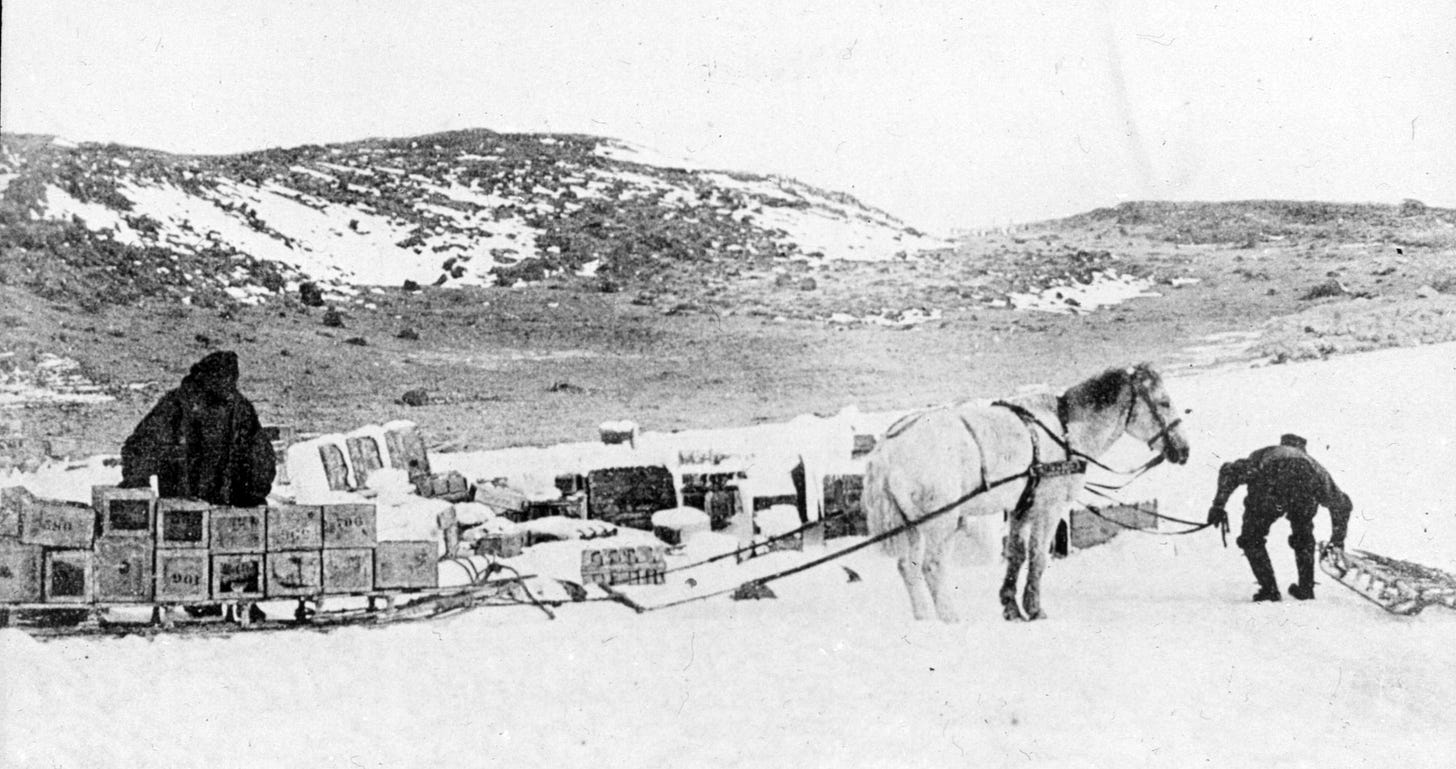

Peary was no stranger to the ice, having spent several seasons traversing the Arctic, but his previous efforts to reach the pole had met with disappointment. Now, in 1909, he had a familiar, well-equipped ship, Roosevelt, and the full backing of the US government. Setting out from Ellesmere Island on March 1—not, unlike most expeditions, in summer, but under conditions better for dogsledding—Peary and two dozen men, nearly twelve dozen dogs, and nineteen long sleds traveled northward, establishing camps here and there and leaving behind caches of supplies and men to make the expedition lighter and smaller the farther it traveled.

In early April, the expedition was down to Peary and Henson, along with four Eskimo guides. That contingent of only six men planted the American flag on the North Pole on a windy April 6, 1909.

Peary returned to the United States expecting a hero’s welcome, only to find that a man who had served as a physician on one of his earlier expeditions was now claiming to have reached the North Pole a full year before Peary and Henson.

Frederick Cook claimed to have photographic evidence to back his assertion. It took more than two years to determine that the photographs were faked. Cook would soon serve prison time for his role in an oil swindle, while Peary could not rest on his claim to have discovered the North Pole until 1911, when a congressional committee finally declared that his claim was correct. (Surprisingly, Cook has his champions to this day.) Peary retired that year, worn out from the fight and from his years of traveling. He died a decade later, and he is now buried in Arlington National Cemetery, that shrine of heroes, with Matthew Henson alongside him.

In the 1980s, a team of Arctic scholars examined Peary’s expedition diary and retraced his steps. They determined that Peary, through honest mistakes of navigation and record-keeping, fell some 50 miles short of the pole. The revisionist account has not been universally accepted, and so Peary’s place in the history books still stands, though with an asterisk. That mark, even if it becomes permanent, does nothing to diminish the bravery of Peary, Henson, and their native companions, who stand enshrined, along with Ernest Shackleton and his men, in the annals of polar exploration and the remarkable year of 1909.

A Greener Greenland

A thousand years ago, a Viking named Eirik the Red, on the run from the law in both Iceland and Norway, sailed west until he caught sight of land. He steered his way along a fearsome-looking coast dotted by massive glaciers and mighty icefalls until he found a place that seemed a little more hospitable. He called it Eiriksfjord. When summer came and the country greened up, he explored the coastline and ventured farther inland until fall came, when he returned to his little homestead .

Eirik pondered what to do with all his newfound real estate in that new country, which he discerned was an island—though he did not know that that island was the largest on Earth. He hit on a marketing campaign that went viral among Vikings everywhere: “He named the country Greenland,” the Vinland Sagas tell us, “for he said the people would be much more tempted to go there if it had an attractive name.” So they did, and Greenland, three times the size of Texas, was soon a destination for hundreds of Viking settlers.

The newcomers found a land locked in ice, covered by the second largest ice sheet on the planet, at 2.9 million cubic kilometers bested only by Antarctica’s. So inhospitable was the interior of Greenland, in fact, that the Vikings and the native Inuit peoples alike were forced to turn to the sea for their living. In time, they developed one of the world’s largest whaling industries, hosting fleets from all over Europe and the Americas, while harvesting massive numbers of fish, especially cod and halibut, from the cold waters off the Atlantic coast. Since less than 1 percent of the island was fit for agriculture, Greenlanders developed a diet that was unusually heavy in animal protein, with walruses, seals, reindeer, and even polar bears contributing to the larder. That diet began to change after World War II, when improved fast shipping across the North Atlantic and regular air travel allowed the country to bring in consumer goods from Canada, the United States, and especially Denmark, the European country to which Greenland still belongs, if now only nominally.

A more thoroughgoing change has come over Greenland in recent years in the form of a pattern of climate change that has seen a warming Arctic. One of the effects of this change has been a rapid melting of the Greenlandic ice sheet, a fact that is causing some alarm to low-lying countries on the rim of the Atlantic, since sea levels are projected to rise markedly in the next half-century precisely because of this rapid introduction of water into the sea. So rapid is this melting, in fact, that it is expected that by the end of this decade the seas off Greenland, as well as much of the Arctic, will be ice-free in summer. The addition of so much cold water has also been cooling the Gulf Stream offshore, with negative effects on many oceanic fish populations—including that of cod, the basis for a fishing industry all the way south to Massachusetts that now seems on the brink of collapse.

Greenland has a permanent human population of about 55,000, but at times it seems as if each resident has spun off an industry of his or her own in response to climate change. One area of interest is resource extraction. (This has excited imperial ambitions among a certain treasonous, avaricious American, of course.) Greenlanders have exploited deposits of zinc and silver in earlier decades, but exploration for them has expanded, and meanwhile deposits of lead, uranium, and other minerals have been found, to say nothing of diamonds of very high quality. Land exposed by glacial melting has revealed an abundance of materials that were earlier locked away, as evidenced by a gold mine that opened in 2004 and that has been producing to capacity ever since.

More than a hundred mines have been laid out and are in operation or soon to be so. Like the Arctic in general, these are seen as being of great strategic importance. It is no accident that China has invested heavily in these mining ventures, since that nation is increasingly resource-poor and has no direct Arctic presence, unlike neighboring Russia. One of the largest iron ore mines in the world, for instance, is going online near the Greenlandic capital of Nuuk; it is operated by a British concern, but its principal investors are Chinese.

One consequence of flowing meltwater is the wherewithal to generate hydroelectricity, and Greenland is also taking steps to increase electrical production in several places in the country. The grid is not well developed that far north, but it is conceivable that via underwater lines this electricity can be profitably exported to energy-hungry Europe. Energy on another front has been much in the news in recent years, too: namely, the development of oil wells off the island’s coast, with the possibility of others on the mainland. The Arctic as a whole is well primed for a boom in oil production, and the only thing that has kept Greenland from pushing ahead has been a flooded oil market that has suppressed prices worldwide. It’s a sure bet that when the next oil crunch comes, though, rigs will spring up within sight of Nuuk’s ice-free harbor. And the race for oil has already caused nations to squabble about exact borders and boundaries, since the Law of the Sea establishes that Greenland (and, by extension, Denmark) have exclusive rights to develop resources within 200 miles (322 km) of the coastline.

One unexpected growth area in Greenland’s economy has been in tourism and related industries such as aviation and food service. A thriving ecotourism industry has brought thousands of visitors a year, most of them wanting a look at the island’s mighty glaciers, which, it seems likely, will not be around for much longer. Flights from Nuuk to Kangerlussuaq and points north now shuttle tourists from all over the world to the ice fields. “Glacier tourism,” as it’s sometimes called, has already proven a big draw for New Zealand’s South Island, and developers are hoping to expand the market.

A greener Greenland means other opportunities, including small-scale farming and the development of a forestry industry on an island that now knows only four species of trees and large bushes. Whether it will find a market depends in part on whether the rest of the world’s economies are overwhelmed by climate change or will, as the Greenlanders are doing, find ways to adapt. In whatever instance, it appears that Eirik the Red’s promising name, once a bit of false advertising, is now appropriate to this northerly place.

Books About Vikings

The Viking period lasted for just a few hundred years, from the rise of the seafaring raiders during what has been called, incorrectly, the Dark Ages. During that time, those Vikings ranged over a huge territory, embracing some forty modern countries, sometimes as warriors, more often as traders. One, a woman named Gudrid, lived in Greenland, meeting Inuit people there, saw Native Americans in Vinland, married four times, then took up the cross and traveled to Rome to meet the pope. Now a nun, she returned to Iceland, where she’d started her journeys. Gudrun was not the only accomplished women traveler among her people, though she surely must have been first among equals. You can read all about her in the Vinland Sagas.

After roughly 400 years of Viking raids so fierce that the people of the English coast called their perpetrators “slaughter wolves,” in the 1200s King Haakon of Norway declared that depredations on neighbors were to be abandoned in favor of farming and Christianity. The mandate unsettled many a free spirit. Writes the great Sigrid Undset of the protagonist of his four-volume novel Olav Audunssøn, “He was … aware that he was supposed to show remorse because the murder was considered a sin, even though he couldn’t understand why it was so sinful.” Scandinavians are a generally peaceable lot these days—though see the great Norwegian crime drama Welcome to Utmark for some notably gory exceptions—but it took quite some time to calm them down after the glory days of Valkyries, bearskin shirts, and magic mushrooms, royal edict or no.

One thing that is central to understanding the Viking phenomenon is that the very word Viking is not an ethnic term so much as a kind of class designation that described people who, writes anthropologist Neil Price in his excellent Children of Ash and Elm, were “as individually varied as every reader of this book.” Granted that their worldview took life to be dangerous and subject to termination without much warning, the Vikings were a small-c catholic lot, with women and transgender people joining their armies and fighting alongside berserkers and ax-swinging devotees of Valhalla. The Vikings were also adamantly democratic, willing to serve kings as long as their rights were respected, gathering annually to make collective decisions and trade with one another.

It’s at one such gathering, the Althing in Iceland, that the events recounted in greatest work of Viking literature, The Saga of Burnt Njal or Njal’s Saga, are set in motion. A vendetta that lasts for three generations, beginning in about 960, opens with a drunken slap. Its disaffected recipient, a woman named Hallgerd, allows her husband to be killed because of the slight. Njal, a man of wise counsel and peaceful disposition and the father of the deceased, is caught up in the feud, only to be burned to death for his troubles. The body count continues to mount when Njal’s son Kári sets out on a campaign of vengeance, the sins of fathers being visited on sons until, at last, the whole of Iceland, in exhaustion, decides that enough blood has been shed.

In Last Places: A Journey in the North, a fellow I’m glad to call a friend, Lawrence Millman, travels across the Arctic in the footsteps of the Vikings—the first Europeans, almost certainly, to reach America, though Irish monks may have got there a stroke of the oar ahead of them. Millman’s book is a wonderful blend of the old and new: the Vikings of Grimsey may once have been fond of vendettas themselves, but their later descendants were given to throwing themselves into the sea on losing a chess match, while a couple of islands over—the book was first published in 1990—their still later descendants are exercising to Jane Fonda videotapes. Delicious details come fast and frequent, as when a Grimsey resident, serving seal meat as a restorative, tells Millman that in local belief seals are the souls of the pharaonic soldiers who drowned when Moses parted the waters of the Red Sea. Writes Millman, “certain people refused to eat seal meat because they thought they might be eating boiled Egyptian.” Hunt up a copy and enjoy.

Egill Bjarnason’s lively book How Iceland Changed the World bears a provocative title, and for very good reason: Over a thousand years and more of human settlement, the little island has exercised a disproportionate influence over events. Start with the aforementioned Eirik the Red, who, as a boy, was forced to leave Norway after his father committed “some murders.” Blown off course on the way to the Orkneys, they landed in Iceland. Years later, after killing a few neighbors himself, Eirik decided to have a look around and found Greenland. Some of his party later landed on Newfoundland and established settlements that endured for decades. Why they ended no one can say for certain, but they disappeared almost overnight. Iceland, though, went on to become an important Atlantic entrepôt and, Bjarnason takes pleasure in noting, a nation that, despite the violent past, has never gone to war with another nation and has never had a military—and, as with the Vikings of the past, is multicultural and welcoming of immigrants. I haven’t been there since the late 1970s, but Iceland is most certainly on my to-return-to list.

Please Subscribe

As this fifth year of World Bookcase nears its close, I’m hoping you’ll be inspired to join the list of paying subscribers. Many thanks!